|

Recursive algebraic types in D

September 15, 2014

One of the things D programming language seemingly lacks is support for algebraic data types

and pattern matching on them. This is a very convenient kind of types which most functional

languages have built-in (as well as modern imperative ones like Rust or Haxe). There were

some attempts at making algebraic types on the library level in D (such as Algebraic template

in std.variant module of D's stdlib) however they totally failed their name: they don't support

recursion and hence are not algrabraic at all, they are sum types at best. What follows is

a brief explanation of the topic and a proof of concept implementation of recursive algebraic

types in D.

So what the heck are algebraic types after all? They must have something to do with algebra, right?

In school we spent a lot of time in algebra classes working with functions, equations and searching

for their roots but nobody told us what an algebra, as a mathematical object, actually is.

An algebra is often defined as some set together with a collection of operations on elements of this set.

We programmers and computer science enthusiasts work with types instead of sets (type is a more general

thing than a set btw). So, in school we dealt with some particular examples of algebras. For example,

we used set R (the set of all real numbers) and operations like x+y, x-y, x*y, xy,

-x (negation, let's write it as ~x) etc.

We can write their types as:

+: (R, R) -> R

-: (R, R) -> R

*: (R, R) -> R

~: R -> R

power: (R, R) -> R

...

Each of these operations takes some fixed number of elements of type R and outputs one element of R.

Constants can be thought of as operations taking zero R arguments and returning one, e.g.

42: () -> R

We can also replace R with Q (the set of all rational numbers) and have most of these operations

work on Q. That would be another algebra.

It's crucial that operations take arguments from the same set (type) as results they produce.

That is algebraic. So, encoded in a programming language, a real algebraic type must support recursion.

Otherwise it's just a sum type, discriminated

union, not very useful for encoding expressions, syntax trees, other kinds of trees or even lists.

The list of operations above is already looking very much like a generalized algebraic data type definition in functional

languages like Haskell, OCaml, Agda or Idris. Here is how it's written in OCaml:

type r =

| Add : r * r -> r

| Sub : r * r -> r

| Mul : r * r -> r

| Neg : r -> r

| C42 : () -> r

In Haskell it's essentially the same, modulo currying:

data R where

Add :: R -> R -> R

Sub :: R -> R -> R

Mul :: R -> R -> R

Neg :: R -> R

C42 :: () -> R

Since all these operations provide result of the same simple type R, we can use the simpler

syntax:

data R = Add R R

| Sub R R

| Mul R R

| Neg R

| C42

Note that here we only define names and form (types) of operations, not their real content.

If we change R to Q we get essentially the same type, only renamed. Unlike in math, where

when switching from set R to set Q we also changed the meaning (implementations if you wish)

of functions: from adding / subtracting / etc. real numbers to adding / subtracting / etc. rational

ones. To emphasize the fact that ADT only describes the names and shapes of algebra operations,

we can replace occurences of R in operands by a type variable:

data F a = Add a a

| Sub a a

| Mul a a

| Neg a

| C42

In order to encode a particular algebra with such operations we need, besides this definition,

a type T of values (the algebra carrier) and an evaluation function

eval : F T -> T

This function will do a case analysis ("which operation is encoded?") and perform the operation,

because it knows well how to add, multiply, negate and so on values of this type T.

Now let's recall some category theory. A category consists of a collection of objects and a collection

of arrows (also called morphisms) between those objects, with some required properties regarding

their compositions and identity morphisms. We're interested in a category where objects are types

and arrows are functions so that each function f with argument of type A and return

value of type B

is an arrow from A to B, i.e. f : A -> B.

A functor is a mapping from one category to another, it maps

objects of one category to objects of another and the arrows are mapped correspondingly, so that

all the compositions remain. Functor mapping a category to itself is called an endofunctor.

The parameterized type F above is such an endofunctor: any type X it maps to type

F X, and any

function g : X -> Y can be trivially mapped to a fuction

fmap g : F X -> F Y

(Haskell compiler can derive the implementation of fmap here)

Now let's look at definition of F-Algebra in category theory. It consists of

three parts: an endofunctor F, object T and a morphism from

F(T) to T. These are exactly the three things mentioned above that

we need to encode some particular algebra. No wonder.

Ok, one more thing before we get to code in D. Recursion. Describing a functor like F above

is simple but we want the type to be recursive: operations like Add should have operands

of same type as their result. Their operands' type is described by type parameter a,

their result is F a, and they somehow must be equal. I.e. we need to find a type X

to be used as type parameter to F such that

F X = X

Looks like we need the fixed point of F. Turns out we can define it quite easily. In Haskell

it looks like this:

newtype Fix f = Fx (f (Fix f))

together with unwrapping operation

unFix :: Fix f -> f (Fix f)

unFix (Fx x) = x

and in D it looks like this:

struct Fix(alias F) { F!(Fix!F) unFix; }

F, being a functor, shall be some struct or class template, so we pass it by alias.

(Higher kinded types? we can has them!)

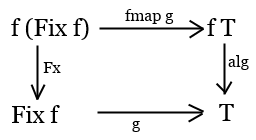

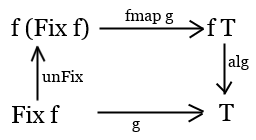

For any endofunctor f, Fix f is a type, an object in our category. This functor, this object

and the arrow Fx: f (Fix f) -> Fix f together form an F-algebra. Category theory says

this F-algebra is special: it's the initial object in the category of F-algebras for this functor,

which means for any other algebra for this functor (say, object T and its evaluator arrow

alg: F T -> T)

there is a unique morphism g from initial algebra Fix f to T,

such that this diagram commutes:

(commutes - means the two paths from f (Fix f) to T are equal)

Knowing that unFix is the inverse of Fx we can actually define g

via unFix, fmap g and alg.

This unique morphism from initial object is called catamorhism, so we'll call it cata with

alg as its parameter.

In Haskell it looks like this:

cata :: Functor f => (f a -> a) -> Fix f -> a

cata alg = alg . fmap (cata alg) . unFix

And in D it looks like this:

T cata(alias F, T)(T function(F!T) alg, Fix!F e) {

return alg( e.unFix.fmap( (Fix!F x) => cata!(F,T)(alg, x) ) );

}

F is a functor and hence has fmap function defined.

Having the catamorphism allows us to easily define different evaluation functions for our recursive

algebraic type from their non-recursive versions defined for particular algebras. I think it is time

to look at the code with some examples to understand how that works. For simplicity let's take a very tiny

algebra: it will contain integer numbers and one addition operation. Something like this:

data Exp = Add Exp Exp | Const Int

Algebraic data types usually consist of a sum of products. Product types we had in C-like languages for ages: structs

and classes. Sum types D doesn't have built-in, but we can make them with templates. The simplest sum type would

be a sum of two types, A and B, known in Haskell as Either a b. Its implementation as a discriminated

union is very straightforward, with one twist:

as shown above, we really need a functor, a template in D, and the summands must have a type parameter too, so they

will be also templates. I'll also add a match function to do familiar by functional languages pattern

matching on the values. Here's how our Either will look in D:

// A and B are class(T) or struct(T) implementing fmap

template Either(alias A, alias B) {

class EitherImpl(T) {

enum Tag { kA, kB }

Tag tag;

union {

A!T vA;

B!T vB;

}

this(A!T a) { tag = Tag.kA; vA = a; }

this(B!T b) { tag = Tag.kB; vB = b; }

U match(U)(U delegate(A!T) fa, U delegate(B!T) fb) {

final switch(tag) {

case Tag.kA: return fa(vA);

case Tag.kB: return fb(vB);

}

}

EitherImpl!U fmap(U)(U delegate(T) f) {

return match(a => new EitherImpl!U( a.fmap(f) ),

b => new EitherImpl!U( b.fmap(f) ));

}

}

alias Either = EitherImpl;

}

The functor for our little algebra of expressions will be defined as a sum

alias Exp = Either!(Add, Const);

where the two summands are

struct Const(T) {

int x;

mixin Functor!(Const, T);

}

class Add(T) {

T l, r;

this(T a, T b) { l = a; r = b; }

this() {}

mixin Functor!(Add, T, "l", "r");

}

The mixin Functor line plays the same role as (deriving Functor) in Haskell.

It's a piece of metaprogramming in D to define fmap methods:

mixin template Functor(alias F,T, Vars...) {

F!U fmap(U)(U delegate(T) f) {

static if (is(typeof(this)==class))

auto r = new F!U;

else

auto r = F!U();

foreach(m; __traits(allMembers, typeof(r)))

static if (m != "Monitor" && m != "fmap") {

static if (IndexOf!(m, Vars) >= 0)

__traits(getMember, r, m) = f(__traits(getMember, this, m));

else

static if (!isSomeFunction!(typeof(__traits(getMember, r, m)))

&& isAssignable!(typeof(__traits(getMember, r, m))))

__traits(getMember, r, m) = __traits(getMember, this, m);

}

return r;

}

}

It's ugly but only needs to be defined once. For a class or struct template F!T it defines a method

fmap that can take any function f of type T -> U and make a similar

object or struct of type F!U where given fields will be mapped by function f while

others will be simply copied.

After having a functor Exp defined using Either we need to turn it into a recursive type

by using its fix point:

alias FixX = Fix!Exp;

alias Exprec = Exp!FixX;

A small helper for creating its values would be handy:

auto mk(alias T, Xs...)(Xs xs) {

static if (is(T!FixX==class))

auto x = new T!FixX(xs);

else

auto x = T!FixX(xs);

return FixX(new Exprec(x));

}

Now we can create some expressions in our little algebra:

auto n1 = mk!Const(5);

auto n2 = mk!Const(7);

auto e1 = mk!Add(n1, n2);

auto e2 = mk!Add(mk!Const(30), e1);

// e2 is (30 + (5 + 7))

What do we do with them? We'd like to calculate expressions to some int results and we want to output expressions

as strings. Each operation can be described as an algebra with int or string type as its carrier and corresponding

evaluation function from Exp!int or Exp!string to int or string. Here they are:

//alg : f a -> a, for some concrete a

int eval(Exp!int e) { return e.match(a => a.l + a.r, i => i.x); }

string show(Exp!string e) {

return e.match(a => "(" ~ a.l ~ " + " ~ a.r ~ ")", i => i.x.text);

}

They use pattern matching by passing to lambdas to match: one that tells what to do with Add case

and one that tells how to process the Const case.

These are not recursive and describe just one step of computations.

Now we can use our catamorphism to apply them recursively and turn such function of type f a -> a

into function of type Fix f -> a which will give us desired results:

cata(&show, e2).writeln; // => (30 + (5 + 7))

cata(&eval, e2).writeln; // => 42

Voila!

The full source code, compilable and runnable, can be found

here on dpaste.

tags: programming

|